West High’s Summer Book Talk Features Special Guest

Art/Photo by Philip Lam

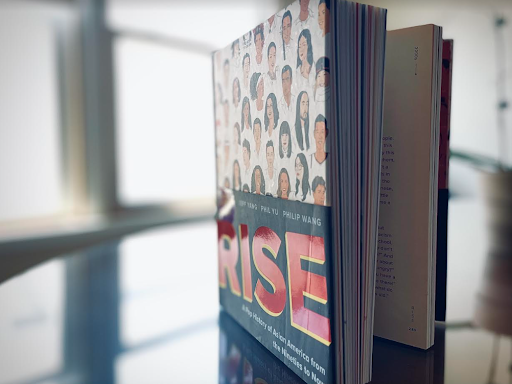

To kick off the school year, students from all grades came together on the first of September to discuss their summer reading books. In Mr.Cheung’s room, a special guest visited the class: Phil Yu, co-author of Rise, to discuss contemporary Asian-American culture through graphics, illustrations, and text.

September 12, 2022

In its widely anticipated return after being placed on an indefinite hiatus, the annual summer reading book discussions were held on September 1st during Warrior Workshop. One of the sessions, hosted by Mr. Cheung, featured a special guest appearance. Prominent blogger and co-author of Rise, a nearly 500-page collaborative piece on the Asian American experience, Phil Yu was invited to discuss his book, its lessons, its cultural impact, and its contribution to the broader Asian-American identity.

In what Yu described as “not your conventional history book,” Rise examines the diverse and multifaceted aspects of Asian American communities spanning the last three decades, a pivotal time when second-generation Asians had to grapple with the notion of what it meant to be “Asian American,” a relatively new umbrella term coined in the late 1960s.

Yu briefly outlined the process of conceiving and penning Rise, recalling how he and his fellow authors, Jeff Yang and Philip Wang, had a “literal spreadsheet in front of [them] over Zoom” to brainstorm ideas that would eventually become central topics for the piece. In addition, Yu elaborated on the various interviews they conducted, convincing dozens of celebrities and illustrious figures to become ad hoc contributors to Rise, from actress Ming-Na Wen to rapper MC Jin.

Rise extols the great strides Asian Americans have made in contributing to popular culture, something Yu contends has often been depicted superficially by Hollywood, with popular perceptions making “it sound like the Joy Luck Club came out in 1993, Asian Americans did nothing, and then Crazy Rich Asians came out [in 2018].”

Multiple students attending the seminar shared similar sentiments over the apparent scarcity of Asian American coverage in popular culture: “[Rise] was like from a different time. I never heard of these references,” recalled Jodie Cheng (11). Cheng expressed her surprise over “the sheer amount of Asian American representation in … movies and shows,” inspiring her to watch the critically acclaimed and poignant drama, The Joy Luck Club, for the first time.

Conversely, Rise equally chronicles the historic misperception of Asian America, in part because “our collective understanding of Asian American history is so shallow,” observes Yu. The implications are massive, but often pernicious, with Shinzo Irie (11) detailing how seemingly innocuous approximations of Asian languages, most notably, the onomatopoetic phrase, ching chong, have caused his “mental image [to] shatter” at times because of its racist connotations. For many students, Rise observably struck a personal chord with them, eliciting both nostalgia and contempt towards the events, institutions, and people that have molded the Asian American identity, for better or worse.

To that end, Yu enlisted broader goals for the audience. Dedicating Rise to “the ones who come next,” the author exhorted that he “want[s] people to know their history.” Similarly, Mr. Cheung commented on how narratives are “a powerful way to hold a mirror to society [and] to ourselves,” warning that “if you take away culture, you take away humanity.” Cheng proposes that more people need to come forward with their stories “as writers, filmmakers, artists, … and as creatives in the entertainment industry.” All agree that Rise is an indispensable agent of culture that has contributed to an increasingly broader and more accurate syllabus of Asian America as a whole.