The Race to Relief

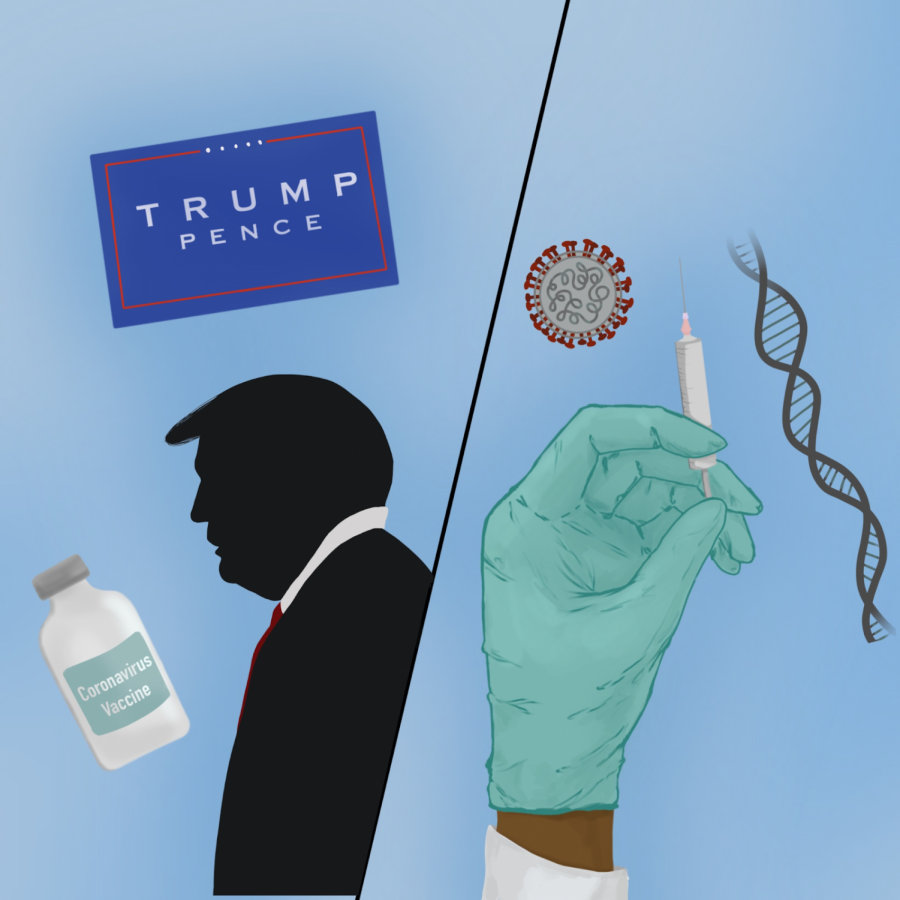

Art/Photo by Samantha Takeda

The recent rise in COVID-19 cases nationwide and political pressure from the Trump Administration raises political and ethical concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine coming before the November election.

October 27, 2020

With the surge of COVID-19 cases in 35 states and hospitalization in 36, the need for a vaccine has become increasingly demanding. But with political pressure and the urgent situation of the world, when will a solution be found?

Vaccine development is usually a lengthy and complex process, taking between 10-15 years. But Operation Warp Speed, started by the Trump Administration, has already spent over $10 billion to aid vaccine makers in pursuit of its goal to produce 300 million vaccine doses by January 1st, 2021.

A few developers engaged in the operation include Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Moderna, and Novavax. These frontrunners are accelerating their work by utilizing new technology that gives them more advantages than conventional vaccines. The classic types are inactive or weakened vaccines. These vaccines have been used safely and effectively on humans to date. But it takes longer to create mass quantities of the virus to be distributed.

Two types of genetic vaccines are now being looked into: mRNA and DNA. Instead of using the virus itself, these vaccines use small parts of the virus’ genetic information to stimulate the immune system to create proteins that will fight the infection. Companies, such as Moderna, which is in its phase-three clinical trials, find that they are quicker to produce. Also, they can be stored at room temperature without losing their activity while traditional vaccines require refrigeration. Unfortunately, there are no FDA-approved genetic vaccines, so it is unknown if they will affect the virus.

One of the first authorized drugs for emergency use was antiviral medication remdesivir, which was used to treat severe COVID-19 infections. Early studies showed the treatment shortened the recovery time in patients from 15 days to 10 days. But on October 15th, the World Health Organization found that drugs such as remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, and interferon showed little to no effect on patients’ mortality.

These companies have also been receiving significant political pressure from the president and his administration’s press conferences. President Donald Trump has repeatedly stated that they will distribute a vaccine before the November 3rd election, explaining, “I’m doing it fast because I want to save a lot of lives.” But after the FDA increased the required one month of observation to apply for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), Trump deemed it as a “political hit job” because it made it harder to get a vaccine before the election. And on Friday, October 16th, Pfizer announced they would not seek EUA until the end of November, fizzling the president’s last best hope for hitting the deadline.

With this political agenda in mind, Science Olympiad member Sorina Yang (10) expressed her concerns, “With many thinking that Trump is using this vaccine for political gain, the public will feel skeptical of the actual safety and effect of the vaccine.” Also, two of the frontrunners, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca, experienced pauses in their trials due to unexplained illness in a few patients, causing more concerns over safety. But according to Mrs. Chambers, one of West’s Biology teachers, this isn’t exactly bad news. She explained, “That’s very normal for a vaccine study. Someone gets sick and you have to find out why. You can’t force time on these [trials] because you have to see if it works.”

She also expressed, “I’m actually very encouraged that the companies that are running the trials are not bowing to the political pressure because I do think a lot of the pressure has been not in the best interest of science or public health.” By taking the time to address these obstacles, vaccine companies suggest they are working towards not only an efficient vaccine but also a safe one to reach herd immunity.

Many doctors hope to achieve indirect immunity when an eventual vaccine is found. Herd immunity occurs when a large percentage of a population becomes immune to a disease such as COVID-19, which in turn protects everyone. By vaccinating most people, it indirectly protects the entire population, including those who can’t be vaccinated such as newborns or those with immune systems that won’t respond to the drug.

But the 50 percent of people reluctant to take the vaccine and 27 percent of people who wouldn’t get the vaccine found in a survey by the Wall Street Journal may undermine this plan.

Mrs. Chambers explained, “I do think there is a contingent of people who don’t understand how a vaccine works well enough. And people often fear what they don’t understand.” She then emphasized the importance of doing research and consulting with reliable sources.

But until a vaccine is found, wash your hands, stay six feet apart, and stay informed.